Dev-Led Landscape: Transforming a Middle-Aged Startup

11 lessons for architects, CTOs, and CEOs who are leveling up a dev-led business within a world of constant change.

I've been on the board of Lightbend, now doing business as Akka, for 5 years and served as its CEO since January.

Venture-backed, deep-tech teenagers face unique challenges that will test the mettle of the board, investors, management and its employees.

The status quo will not deliver results. How do you succeed as a change agent while also bringing forward the successful past?

Akka (the tech and company) is stunning:

Founded by Jonas Bonér, our CTO, in 2011 to support and enhance OSS Akka.

100 blue chip and 200 at-scale startup customers.

Akka has been downloaded 1 billion times across 25K companies supporting 100K apps.

More than 2 billion people touch an app built with Akka every day.

Amazing, global employee talent whose average tenure is >7 years!

Like all companies, Akka also has growing pains:

Experimented, launched, and sunset dozens of projects, products and SKUs.

Multiple brands each with different identities: Lightbend, Akka, Kalix, Cloudstate, Lagom, Play, Cloudflow, Conductor, and Fast Data Platform.

Inconsistent growth with difficult to anticipate, but reasonably low customer churn.

An unsustainable burn rate that didn't provide a high confidence route to profitability.

Rotating sets of middle managers who lacked growth experience and domain know-how.

A lack of market recognition for Akka's achievements and its relevance for the future.

We want to create sustainable, impactful technology and value for all the world’s applications. We want to have a sustainable, growing, profitable business that is valued by our employees, customers, partners, competitors and investors for how our contributions deliver beyond the promises that we make in ways that ultimately make every application - and the world - a better place.

This journey - transformation through innovating on the future while pulling forward your successful past - is similar for most any executive in technology - revenue leaders, architects, CTOs, and CEOs. Developer-led businesses face unique challenges with a user group that is idiosyncratic and powerful. And we are expected to undertake this transformation in a world where information flows continuously and change is constant. How do we survive - and thrive - through such an experience where we are carrying total accountability and limited responsibility?

Here is my leadership recipe, shared with employees, management, customers, and partners.

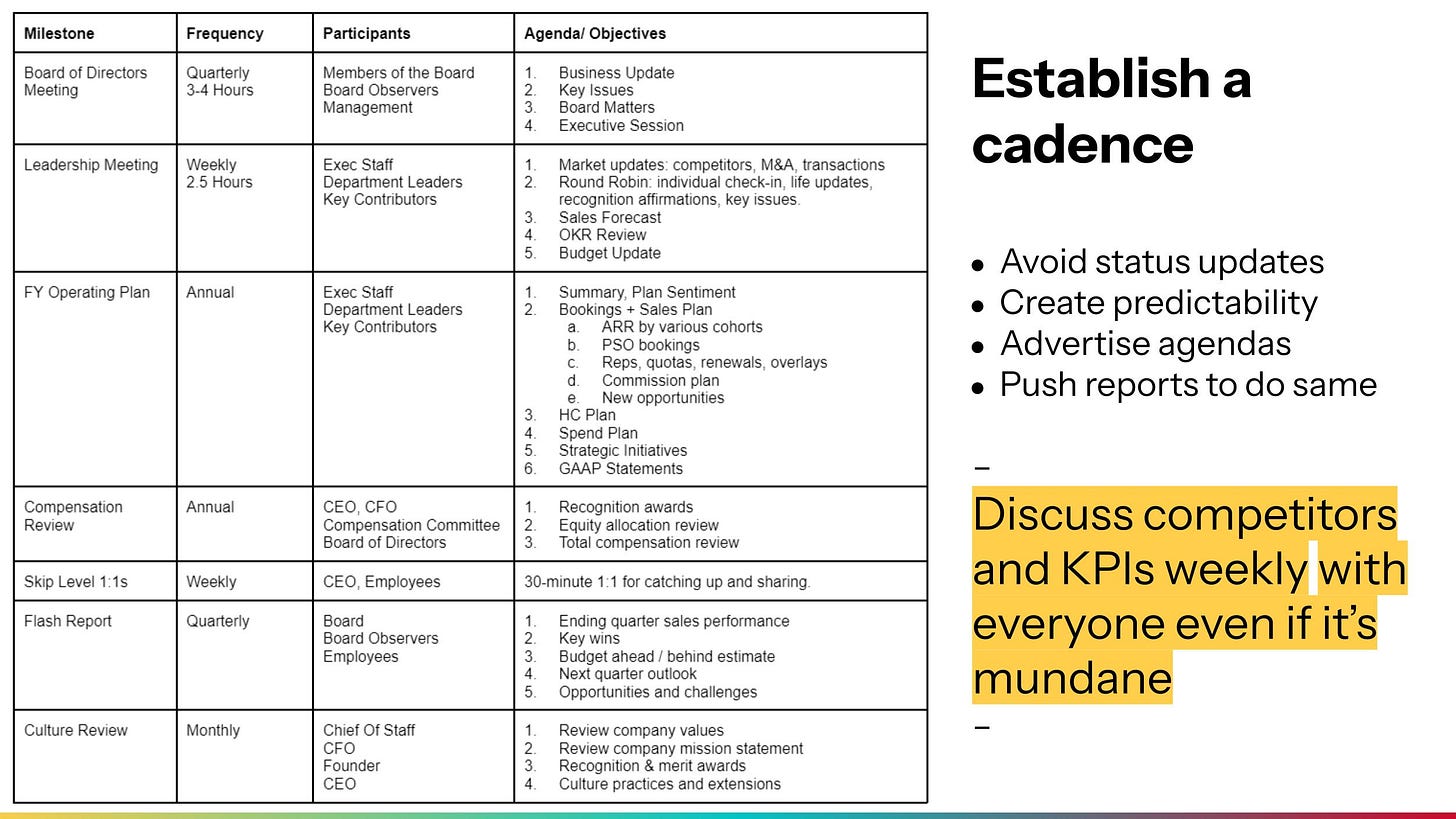

1. Establish a cadence.

Everything within a company should have a regular rhythm to it. All critical matters can be set to a cadence of deliverables, meetings, or activities that are defined in advance. Everybody - management, employees, customers, partners and the board benefit from predictability and then following-through on the cadence. Even soft factors, such as culture, should have a cadence to them. It will be uncomfortable for people to execute within such a structure initially as sometimes the cadence meetings have limited initial content, or others were unprepared for what might happen within the meeting.

These are the meeting cadences that were established in the first month of joining. This table is published in the Akka Business Plan document that is available to every employee.

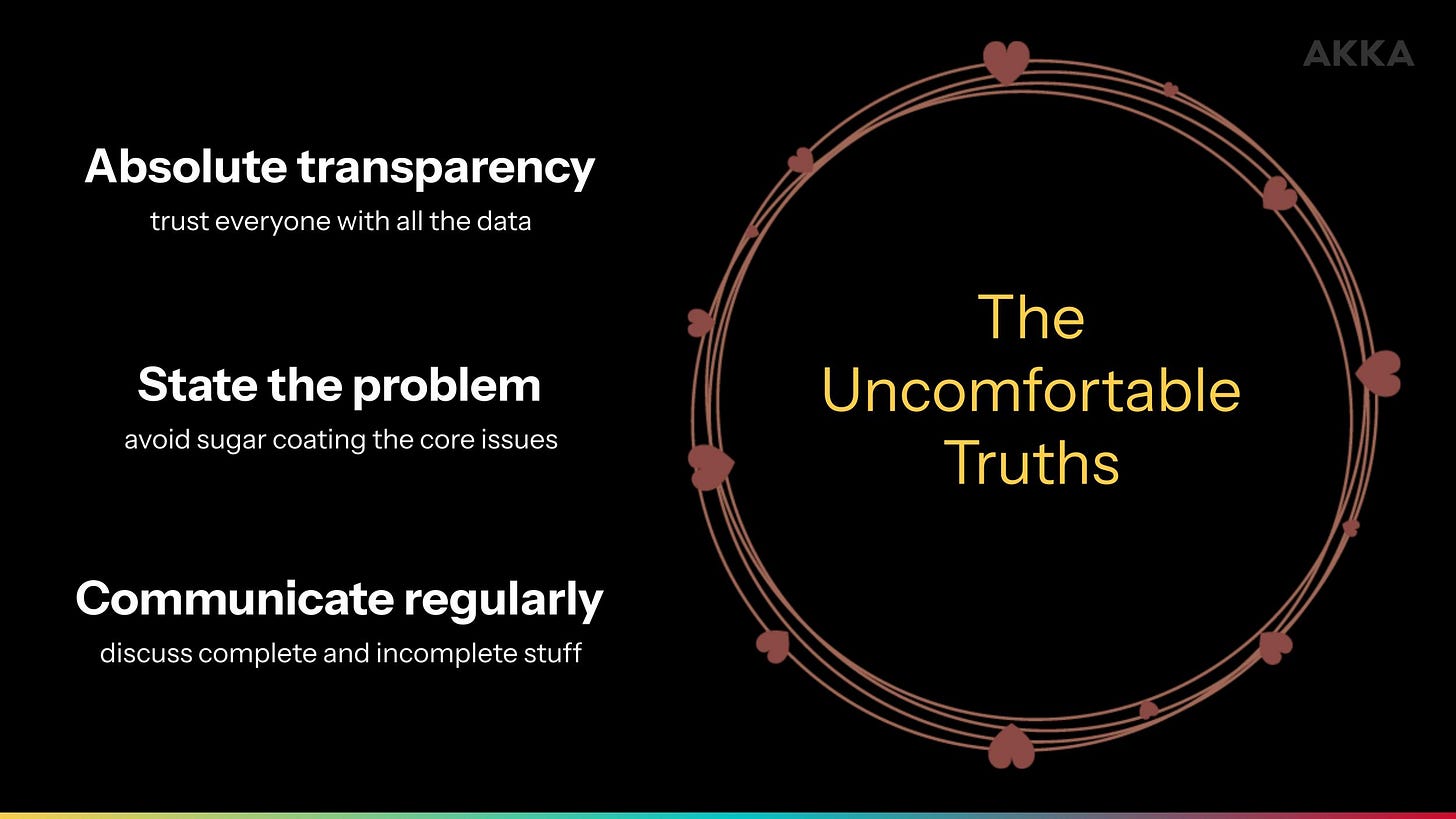

2. Provide absolute transparency.

Unless governed by confidentiality restrictions (and there are very few situations where this is true), share everything with everyone.

It’s part of the human condition to worry about whether employees will be able to understand and interpret sensitive information tied to financials, financing, debt, or strategy changes that can affect employee’s careers or customer relationships. Withholding this information or attempting to package it to be delivered in its most polished form will just foster distrust and questions from employees about what else they are not yet aware of.

I send an email to everyone@Akka.com weekly. I often provide details about major (undecided) strategy elements, good news about successes in the marketplace, or concerns that could significantly impact our business.

We also send our unedited board deck to everyone in preparation for an All Hands meeting that we hold right after the board meeting. This provides additional transparency but also allows for us to get close alignment between the conclusions from the leadership offsite, board meeting, and team meetings, which all take place one after another.

Everyone knows that a new CEO is there to be a change agent. It’s not a surprise to anyone that changes will occur. Provide insights and a channel for everyone to follow along in your plans, thinking and actions, and the change you are making will be enacted faster and more effectively.

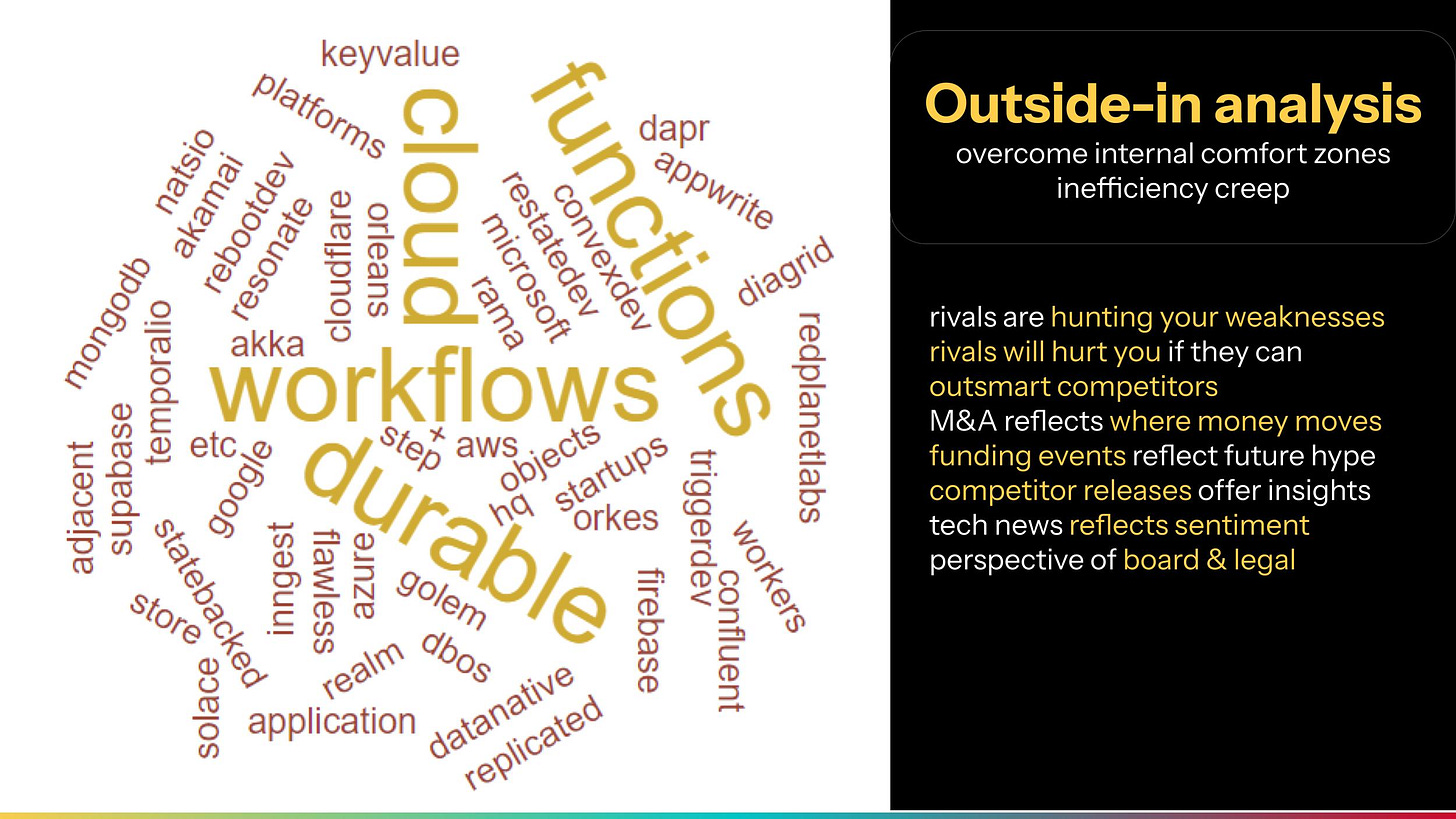

3. Outside-in analysis.

Organizations that have long tenured employees and >10-year operating history have a tendency to execute against a model that has been successful for them. Most decisions and analysis of issues are presented in the context of how the company has historically handled it previously.

This style of management can sustain a company for a very long period of time but ultimately will allow inefficiencies to work their way into the business. Every business has competitors. Your rival’s mission is to destroy you. And if your rivals are filled with people who are dedicated to that mission, then they will discover weaknesses in you or best practices that they can embrace which will make them more efficient. Either way, your rivals will outperform you and by the time you realize your deficit, it may be too late to take corrective action.

The best way to have an organization execute strategies which are going to outsmart your competitors is to be on top of all the world’s best practices. You achieve that by bringing in a culture of outside-in analysis.

It’s rare for a single person to invent an entirely new methodology. Most of the best practices that are having the biggest impact can be observed in the marketplace. Study your competitors and the many companies that are part of the adjacent sector that you are a part of. Everything your organization needs to outcompete and to become more efficient can be learned by looking at what is working well at other companies that you admire.

I keep a database of 1600 DevOps companies (sign up to get the latest updates) that I have been building since 2009 to facilitate this exercise. What are all of the companies in the DevOps space and how do they segment themselves? What are their ARR growth rates? Who has raised the most money recently? How are the employee populations of those companies changing? Who is getting written about the most and why? What are the new products that are being launched and who are the early customers purchasing them? What executives have changed allegiances and joined new companies?

Every answer to these questions offers insights into what is happening in the market and there are lessons that everyone in the company can learn from.

This type of thinking and then understanding how to take lessons from other companies to apply to your own will be unnatural for many in the company. It takes time and many exposures to this type of thinking before they get comfortable doing it daily.

It’s for this reason why we allocate nearly 30 minutes in the bi-weekly leadership meeting dedicated to reviewing all of the market events that have the potential to affect our business, even if only tangentially.

If you have a board and they have investors, leverage their insights to facilitate this thinking internally. The job of a VC is to stay connected to the many deals that are happening daily. They live by framing an understanding of what trends, successes and failures that are happening throughout the market, and they should always be able to frame your business relative to the outside world.

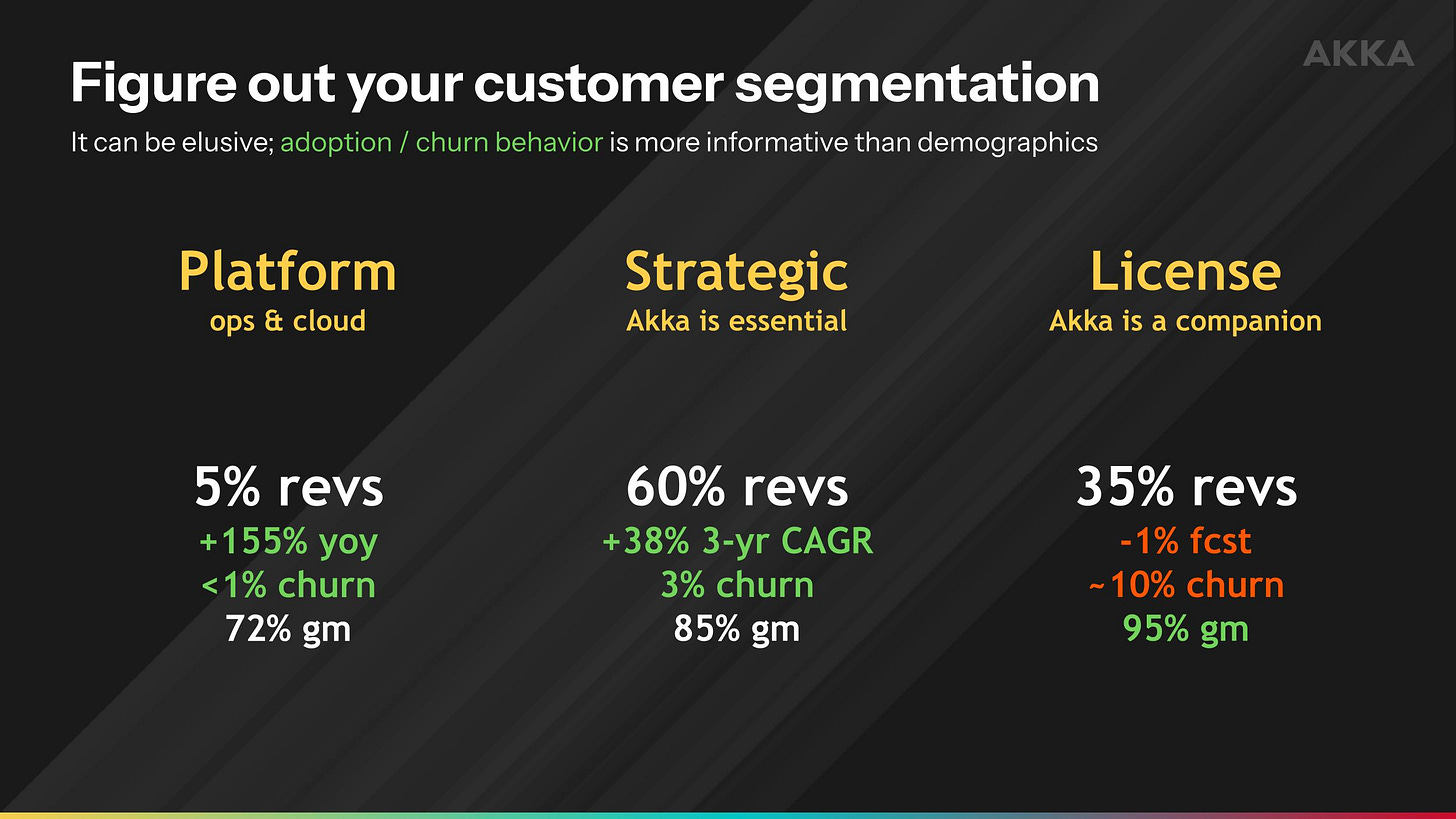

4. Figure out your customer segmentation

Whether you have 10 customers or 10,000 customers, you need to understand your segmentation. Most businesses struggle to pinpoint what segments their customers represent as there are 100s of legitimate ways to segment a customer base.

Do you slice by size? Do you slice by region? Do you slice by product? Do you slice by contract scale? Do you slice by profitability?

You have not figured out your customer segmentation until you can place all of your customers within a bucket and - with minimal explanation - have employees, board, and investors entirely understand the evaluation, buying, support, and sunsetting behavior of each segment. If it takes you 5 minutes to explain the behaviors of a segment, then your segments are wrong.

Customer segmentation will inform you of how to organize and structure your business processes, field programs, customer support, demand generation, and roadmap initiatives.

You must review every customer’s history. You must understand the behavior behind every churn. You must understand the varying ways that customers discover you and move through their customer journey. You must have a sober understanding of their motivations.

You can rarely get your customer segmentation accurate on the first attempt. Every customer must fit within a segment cleanly, clearly. If they do not, then you haven’t figured it out. Keep pressing your teams until they can frame it succinctly.

You will know whether your segmentation is correct based upon how quickly outsiders and board members grok the segments and behaviors.

This is the segmentation that we unveiled in our latest board meeting. This alignment was so easy to understand that everyone will want to understand the underlying behaviors driving each segment. Moving forward, these segments will be tracked as separate P/Ls with ARR waterfalls to track total accounts, additions, upsells, down sells, and churn.

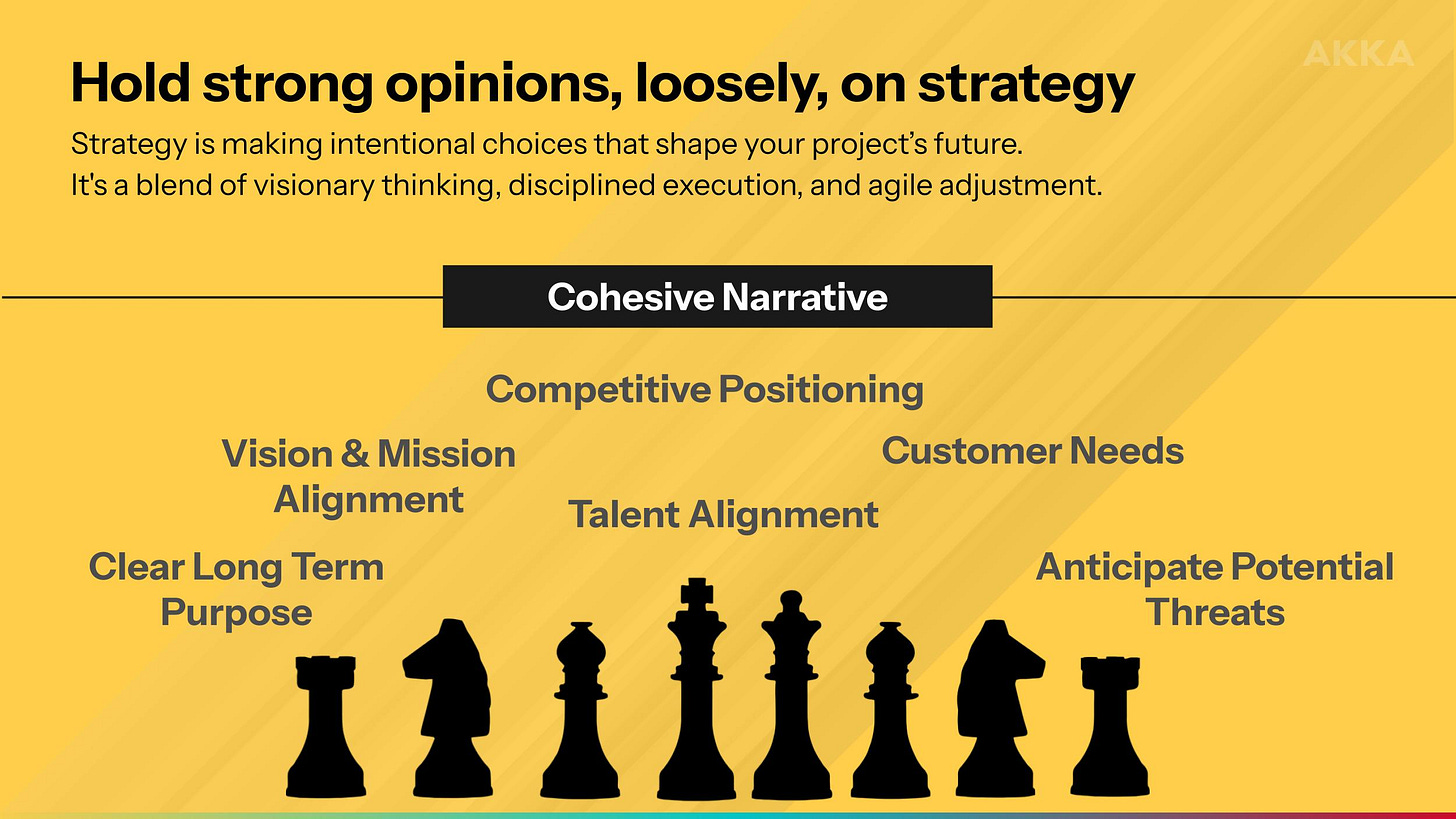

5. You must hold strong opinions, held loosely on strategy.

Strategy is the set of decisions that guide a company’s long-term direction and how it will allocate resources, compete in the market, and achieve its goals. It's not just about reacting to immediate challenges but crafting a vision for the future and ensuring the organization moves toward it effectively.

The most critical elements of strategy include vision and mission alignment; setting a clear long-term purpose; competitive positioning to frame and understand market opportunities, customer needs and differentiation to create sustainable advantages; risk management by anticipating potential threats from market shifts competition or regulation; establishing how a company will be adaptable to unforeseen changes while balancing consistency; and ensuring that the company’s culture and talent align with strategic objectives.

Ultimately, strategy is about making intentional choices that shape the future of the company, rather than letting market forces dictate direction. It's a blend of visionary thinking, disciplined execution, and agile adjustment.

Much of this must and can be sourced throughout the company, but it’s challenging to bring many strategic elements together into a cohesive, uniform narrative. The entire executive team is responsible for achieving this, but ultimately the CEO is responsible for ensuring that the strategy exists, that it’s cogent and clearly articulated, and that it accounts for the spectrum of the business.

In a middle-aged company, it has gone through multiple iterations of strategy, some successful and others not. It’s not always the case that an incoming CEO would need to alter strategy, but if recent performance has missed expectations, then the strategy needs to be evaluated within that context.

It’s typically going to be the case that the CEO has to articulate and recommend alterations to the strategy. It can sometimes surface from within the leadership team if they are given a private, safe space, but their long-term tenure has often made them deeply aware of the company’s internal machinations, but less aware of best practices exercised by peers, rivals, or adjacent businesses.

As the CEO, you have to push for strategies, get them documented, and then test them against many litmus tests. Many strategies will be challenging to understand or impact the status quo.

The CEO frequently has to be a proposed strategy’s chief cheerleader, sometimes passionately so, even if the strategy has many unacceptable risks. You have to advocate for the strategy and lay out strong opinions to those around you. If you do not do this, then the organization may not create the space necessary to fully exercise the strategy and weigh its various merits (or demerits). It’s only when a strategy is tested with the full intellect and time space from the organization’s strongest thinkers, customer advocates, and engineering innovators that you will understand the depths of how that strategy can hold up if executed in the market.

These discussions will be challenging, and most strategies will fail. Therefore, you have to go in as chief cheerleader, perhaps creating an environment of discomfort, in order for the strategy to be fully tested against its potential. The consequence of this approach is that you have to be on high alert for data, perspectives, or arguments that point to the strategy being insufficient, poorly constructed, or one that will succumb to competitive pressures. When this happens, you must have a loosely held approach to the strategy, recognizing that the leaders and organization have unlocked critical aspects that show the strategy will not work.

Let go of whatever excitement came with that strategy, pivot, find a different strategy and then re-test with the team repeatedly until you have worked out a strategy that withstands the stresses that you have thrown at it.

It took us multiple iterations over 6 months for us to document our strategy:

Transform Akka into the leading vendor for building and running responsive applications.

To be the first vendor ever to offer customers a guaranteed resilience SLA for their applications. For global digital business to require Akka elasticity, agility, & resilience in order to deliver responsive {Digital, Customer, Data, User, & AI} experiences.

To deliver this promise through growing the Akka ecosystem, transforming our beloved toolkit into an operator platform, and delivering an innovative DevEx for distributed systems.

6. Simplify.

It’s become a running joke that people hear me say in meetings, “it’s easier to scale one thing than to scale two.” I say this because it’s true.

Whenever there are multiple things within the company, ask whether it can be simplified.

Simplification is a hard, often brutal, goal to achieve. Successful products, brands, programs, and technology are successful for a reason. The process of simplification forces the company to address difficult trade-offs that will have consequences. Simplification may force you to stop helping a lesser issue in order to help solve more important issues. Simpler is always a way of saying, “doing less to achieve more”.

One positive consequence of having a relentless approach to simplifying the business is that simpler things are easier to communicate. If they are truly simple, then everyone - employees, leadership, customers, partners, board members and investors - will embrace and support the new approach. The time to get alignment is shorter, albeit the discomfort that comes from having to let go of favorite historical things that were not simple will linger.

Simplification and the path to achieve it will not always be apparent.

We made a decision early that we would be consolidating our many brands down to a single, globally recognized brand. This was an easy choice and garnered the support of everyone immediately. The work to map our many packages and products to work within a single brand began immediately and the mapping had initial, logical pathways.

As we began the process of collecting feedback from the market, strategic customers and analysts, we were uncovering tensions in the role, targeting, and differences that would exist between the two products that we’d take into the market. The product segmentation wasn’t intuitive and cut clean and that was being surfaced through challenge questions that were requiring paragraph explanations.

Our brand simplification had introduced product complexity.

We ultimately saw this as an opportunity and then made an even bigger leap - could we simplify our many products down to one? Are we really a multi-product company? Are we a company that is targeting different audiences or one? Are we a company that requires many different price points or is there one?

If you want to be simple, then be simple - one brand, one mission, one product, one pricing model, one target user. Keep it simple. Target a massive market. Have a clear, simple differentiation that cannot be easily attacked. The path and way to achieve this will not be intuitive. Keep sorting through all of the questions until you find the way. It will eventually emerge from the many insights that exist throughout the organization into a simplification that (when everyone looks back) will ultimately cause everyone to go, “well, duh, of course.” We went through that process and will soon have a coming out party.

Wait until our customers and the market sees what we become. Our teams are excited, and this simplification will ultimately allow us to grow more efficiently.

7. Details matter, it is not micromanaging.

If a micro detail of the business can affect the makeup of the strategy or the organization’s ability to execute on the strategy, then the details and specifics are crucial to be elevated, reviewed, and brought in line with the company’s direction.

There is no detail that is too microscopic that doesn’t deserve the attention of the leadership team if it has the potential to affect how the strategy comes to fruition.

This has the potential to ruffle any number of feathers throughout the company. You must get involved, regardless, as any splintering of the micro details apart from the direction the company is heading will ultimately undermine the company’s chances of success.

You should only engage when you have a clear understanding of how the topic affects the company’s direction. Unfortunately, you may not always be able to articulate the reasoning why clearly and that you have to get immersed within the details of the issue before you can concisely articulate how the issue is connected to strategy. Trust your instincts and previous experiences within the business world to guide you on whether something that is happening is problematic even if you cannot yet frame the issue effectively. Your inner voice is leading you for a reason.

Much to the chagrin of different team leads, I’ve had an over-active participation in working through certain tactics as it relates to:

how our toolkit will evolve into a platform

how docs must be structured (if you are running a company with a focus on developers, subtleties in what the docs deliver affect how devs perceive our product)

the company’s rebranding

the analyst pitch deck

the nuances of pricing / packaging

GTM KPI tracking

demand generation (audience, flywheel tactics)

I only engage until I am confident that the strategy is well-formed, and the approach being taken to this critical area of the business is consistent and aligned with the direction that the company is heading. If there is a challenge with the approach being taken or that the details are not well aligned to the strategy, then I stay engaged until the details are clear and aligned. This is not micromanaging, it’s ensuring alignment.

8. Do not wait.

There will be dozens, maybe even 100s, of changes that the organization will need to undertake in order to execute the strategy or react to changing market conditions.

The nature of middle-aged startups is that there are teams, and perhaps teams of teams. Everyone wants and should have a voice, especially if a change is going to impact customers, their job, or the culture.

Organizations are filled with people who are both risk takers and those that are more cautious. If you wait for complete consensus on every decision then there is a tendency for the cautious to have their concerns amplified in ways that can slow, or even paralyze execution.

You are there because the organization must change. If the decision is aligned to the strategy and obvious that the company must undertake it despite its many risks, then do not wait for the cautious objectors to get on board. Push, press, act, and, if absolutely necessary, demand for the change to go through.

The cautious objectors are an essential part of the business as they often embody the company’s historical DNA (i.e., they know where the bodies are hidden), but they will also consume too much of the company’s resources while going through an organic approach in order to get comfortable with the changes that are being considered. If you layer in a large, diverse leadership team and distributed operating teams, giving everyone the time to contemplate and share their voice on critical issues facing the company will allow lackadaisical decision making to permeate in ways that create permanence when agility is necessary.

Resist inflexible behaviors whenever they crop up. Create a sense of urgency on every possible decision. On the decisions where the path is obvious, albeit controversial, do not wait and press the teams to surface objections immediately or to execute.

Many leaders and people within the company will often not allocate the intellectual and research efforts necessary on a major change until you have forced a dedicated meeting, offsite, or leadership discussion on the topic. There have been topics within Akka that were floated for more than two months and while the cautious objectors would periodically ask questions, they were also not working through the details in a constructive way to overcome their concerns and bring the decision to a conclusion one way or the other. This is potentially devastating behavior for a company to accept.

Do not wait and push for execution and resolution, unless someone raises a critical issue or perspective. But you will find that often these critical issues will not be discovered until the group is being instructed to make it happen.

A couple years ago Akka decided to change its license from an open source permissive license to the Business Source License. This change was controversial within the community and within the company’s four walls. Two years onward, it’s now universally considered a choice that the company should have made years earlier. This change hasn’t come without its challenges. We have an amazing 13M downloads monthly, but our ability to engage with the community that depends upon our software is <0.01%. If we are unable to engage with the community who are building mission critical systems with our software, then we will be unable to support them and shape the next generation of our technology to better meet their needs. This lack of engagement stems from the historical nature of Open Source Software (OSS) which encourages and allows for anonymous adopters of a technology stack. The leadership team made a difficult decision a couple months ago to alter the motion of our popular software so that we can increase what is known about our community so that we can support them better.

This change will fundamentally alter the motion of how new and existing users of our software learn and adopt the technology stack, and the changes will reverberate through customers, partners and the open source community. Once the decision was made, do not wait - execute on the clear details, communicate clearly to everyone what is happening, but execute like every second delay is business lost.

9. Lead by example.

It sounds cliche, but you must lead by example.

Yes, work ethic is a big part of the example that must be demonstrated, but there are so many other properties that you must live by. If you fail to live by any of these properties, or you complain about them to those around you, then you are not leading by example. Leading by example means that you must both execute them with purpose and quietly accept the negative impacts that they have on your life.

Work ethic. Hustle. Critical thinking. Competitor obsessiveness. Demanding perfection. Learn from mistakes. Coachable (strong opinions, loosely held). Avoid excuses. Committed. Embody a belief in the company. Being the very best in the world at their job.

Am I a perfect CEO? Hell no. I have room to grow, but I approach the job as if my sole responsibility is to be the best damn CEO the planet has ever produced. Any expectation lower than that would be a disservice to this team and our customers.

10. Sort out who is truly committed.

When you have a company with people who have found a long tenure, some are there because they are committed to the mission, and some are not.

A-players are people who are committed to the company’s mission and are also committed to becoming the very best person in the world at their job. Everyone else is just someone that hasn’t yet been coached into an A-player. C-players can sometimes become A-players, but probably should be managed out - quickly.

If you come across someone who isn’t coachable or not truly committed to the mission, then figure out a solution quickly.

When you have people who are not producing results while objecting without providing solutions then you should ask if those people are there for the right reasons. Once you have figured that out, see point #7.

11. Build upon the culture.

When you have a company that has survived for more than a decade, it got there because there were amazing achievements from amazing people.

Those people achieved superior results in part because they loved the work they were doing. People only love their work if they are in an environment that is designed to bring out the very best in their performance. That’s culture and it’s the hidden, most powerful driving force that allows the company to attract the very best talent and to enable them to achieve beyond the limits they thought possible.

An incoming CEO has limited ability to build a new culture, or really, to modify the culture that is there. It’s best to understand the constructs of and build upon the qualities of the culture that are already working.

Culture in a technology company stems from the founder’s beliefs, and they are typically baked into the way the company operates. Many people are unable to articulate those values, but they inherently feel it as they were drawn into close working relationships with the founder. Those values were baked into people who stepped into early leadership roles as they become cultural digital twins of the founder, often without realizing it.

At Akka, many values that people exhibited were unnatural for me. It’s not my place to attempt to change the culture, but instead to embrace it, document the values, and press for ways to have culture incorporated into the daily ways that everyone works.

Jonas has strong views around autonomy that allows for creating a culture that encourages and allows failure in order to fail fast and learn more quickly. This enables natural leaders to be more successful as anyone regardless of title that takes the lead on complicated problems which offers that person a stronger career path. In a software technology business, the iteration cycles to try things and then to fail from them can be quarters rather than days, and so it poses a leadership challenge for the CEO to embrace this level of autonomy and incremental failures in order to extend and build upon the culture. So, it’s the CEO’s job to figure out this balance in a way that builds upon the culture while achieving the targeted goals we are setting out for ourselves.

Jonas originally wrote about a set of operating principles:

Flat organization.

Decentralized decision-making.

Transparency of information.

Embrace failure.

Focus on quality.

Minimum amount process.

Embrace diversity.

Trust each other’s intentions.

Customer-first mindset.

And through a couple quarters of discussion and review, have synthesized them into a set of statements that are a reflection of our unique way of operating. Our HR lead, Nicole Valdez, is then tasked with the incredibly challenging job of making sure that these values are discussed, observed, and practiced in every meeting and interaction that we have internally and externally.

We’re Authentic:

We value transparency and genuine communication, without politics or games. We're honest and assume good intentions, cultivating trust and accountability within our organization and in our interactions with others outside of Akka.

We’re Customer-Focused:

We value customer outcomes above all else. By prioritizing our customers' interests, and meeting them where they are today, we help ensure their success. We are dedicated to deeply understanding our customer’s needs, anticipating challenges, navigating time constraints and striving to exceed expectations.

We’re Nonconventional:

We value fearless innovation by challenging the status quo and embracing alternative approaches. Continuous learning and a growth mindset aimed at improving ourselves, our company, and our products, drives us to push boundaries and explore new solutions. Guided by a bias for action, we leverage industry and customer insights to inspire fresh ideas, enabling optimal future offerings.

We’re Persistent:

We value excellence through continuous experimentation and courageous problem-solving. We recognize that achieving success often demands approaching challenges with tenacity and taking calculated risks to achieve leading-edge solutions.

The before and after.

It has only been a year since joining Akka as its CEO. We achieved three outcomes - driving growth in our licensing business, establishing Akka as a platform for global multi-cloud applications with a corporate rebranding, and achieved cash flow positive operations.

But the work is never done. We are in a world of constant change, and so we must continue the journey forward, transforming continuously, striving towards our vision and delivering on the value points that have brought so many of our team together.

I’d love to hear about your own practices for leadership within a dev-oriented landscape. Tell me about your own journey: tyler@akka.io.